Openness Has Limits

Part 4 of a 5-part series on the politics of preservation and power.

Welcome to the fourth installment of my iPRES keynote series. In Part 3, we discussed the importance of community in supporting infrastructure. In this post, we’ll talk about the myth that is prevalent in the library community: that openness is inherently good.

Thanks for reading! This post is part of my iPRES keynote series, in which I examine the hidden political and cultural structures of our systems. You can explore the rest of the series here:

Part 1: Encountering Collapse

Part 2: The Myth of Neutrality

Part 3: Community as Backbone

Part 4: The Limits of Openness (this post)

Part 5: Collapse as Opportunity

Libraries often talk about openness as a core tenet of our belief system. For many organizations, making knowledge publicly available isn’t a question; we just do it. But we have embedded openness into our core belief system, leaving the idea without governance. And unfortunately, this can lead to exploitation. Transparency and access must be balanced with consent and collective accountability.

The AI era has revealed the challenges associated with openness. What was intended to democratize knowledge—such as “open access” and “open source”—now risks benefiting exploitative companies that are far from neutral, as I mentioned earlier. Libraries need to evolve from being “open by default” to being “open with thoughtfulness.” This entails creating environments in which agreement, governance, and collaboration guide participation. Genuine openness supports the commons through shared responsibility, rather than through indiscriminate exposure.

Katherine Skinner, The Emperor’s New Clothes

In “The Emperor’s New Clothes”, Katherine Skinner reminds us that openness, on its own, is not a virtue. Without governance—without the frameworks that create accountability—openness quickly turns into exploitation. She calls out the illusions we’ve built around open infrastructure, around progress, and equity. What we call “open” often masks hidden hierarchies, unpaid labor, and decisions made behind closed doors.

Skinner’s analysis of funding patterns exposes how this imbalance plays out. We celebrate grant announcements and new features, but rarely question how the underlying infrastructure stays afloat—or who is asked to hold it up. As she points out, most funding goes toward visible innovation rather than the invisible work of maintenance and community building. That’s the paradox of our current ecosystem: it rewards novelty while depleting the ecosystem that makes openness possible in the first place. It treats shared infrastructure like a free beer rather than a free puppy. In reality, many open projects operate in silos, competing for scarce funds and attention while exhausting the people who keep them running.

The alternative Skinner sketches are less about control and more about stewardship. She points to models like HathiTrust that build openness through shared governance and pooled investment. These ecosystems don’t confuse access with equity; instead, they recognize that sustainable openness requires structure and agreement. In Skinner’s framing, governance keeps communities from burning out or being exploited. If we want openness to endure, we have to treat it as a relationship to be tended, not a product to be consumed.

For a long time, we treated openness as an unqualified good—a moral stance that needed no further justification. But the last few years have shown me that sharing alone doesn’t guarantee equity or sustainability. For me, the ideals of openness have collided with reality. The systems that promise collaboration and shared progress can, without governance, reproduce the same hierarchies they were meant to dismantle.

Nadia Asparouhova, Roads and Bridges

We’ve long celebrated transparency and access as the cornerstones of innovation, but in “Roads and Bridges: The Unseen Labor Behind Our Digital Infrastructure”, Asparouhova forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that open infrastructure often disguises exploitation. The open-source ecosystems she describes in Roads and Bridges are built by maintainers who are underpaid (if they are paid at all), overextended, and largely unseen. Meanwhile, the companies and institutions that rely on their work reap the rewards. What we call “freedom” in open infrastructure often hides structural neglect. The same openness that powers collaboration also permits exploitation when recognition and consent aren’t part of the equation.

Asparouhova’s core insight is that digital infrastructure, like physical infrastructure, requires maintenance, governance, and long-term investment to remain functional. Yet, unlike roads or utilities, open-source projects lack coordinated stewardship; they are maintained by small, often unpaid communities or individuals. And to make matters worse, economic incentives, venture capital interests, and cultural norms in software development have created a system in which vast social and commercial value is extracted from the unpaid labor of maintainers. Essentially, “openness” becomes a convenient moral cover for the asymmetries baked into the digital economy. Her framing of maintainers as the “unseen labor” of the internet exposes how open infrastructures reproduce the same inequities we claim to transcend by participating in these communities. It’s not a failure of individuals but of a system that celebrates contribution without ever building structures to acknowledge and value the labor that goes into contribution.

The call that emerges from Roads and Bridges is for a new kind of openness—one that balances labor with acknowledgment. Asparouhova asks us to stop equating open infrastructure with virtue and start designing for durability. We need funding models that honor maintenance, institutions that share responsibility, and communities that consent to the load they carry. In other words, the future of openness depends on re-centering the value of labor. If exploitation is what happens when openness runs without governance, then sustainability — real, long-term sustainability — begins when we practice openness while valuing the labor that helps us create it.

Story Time: The impact of AI on Labor

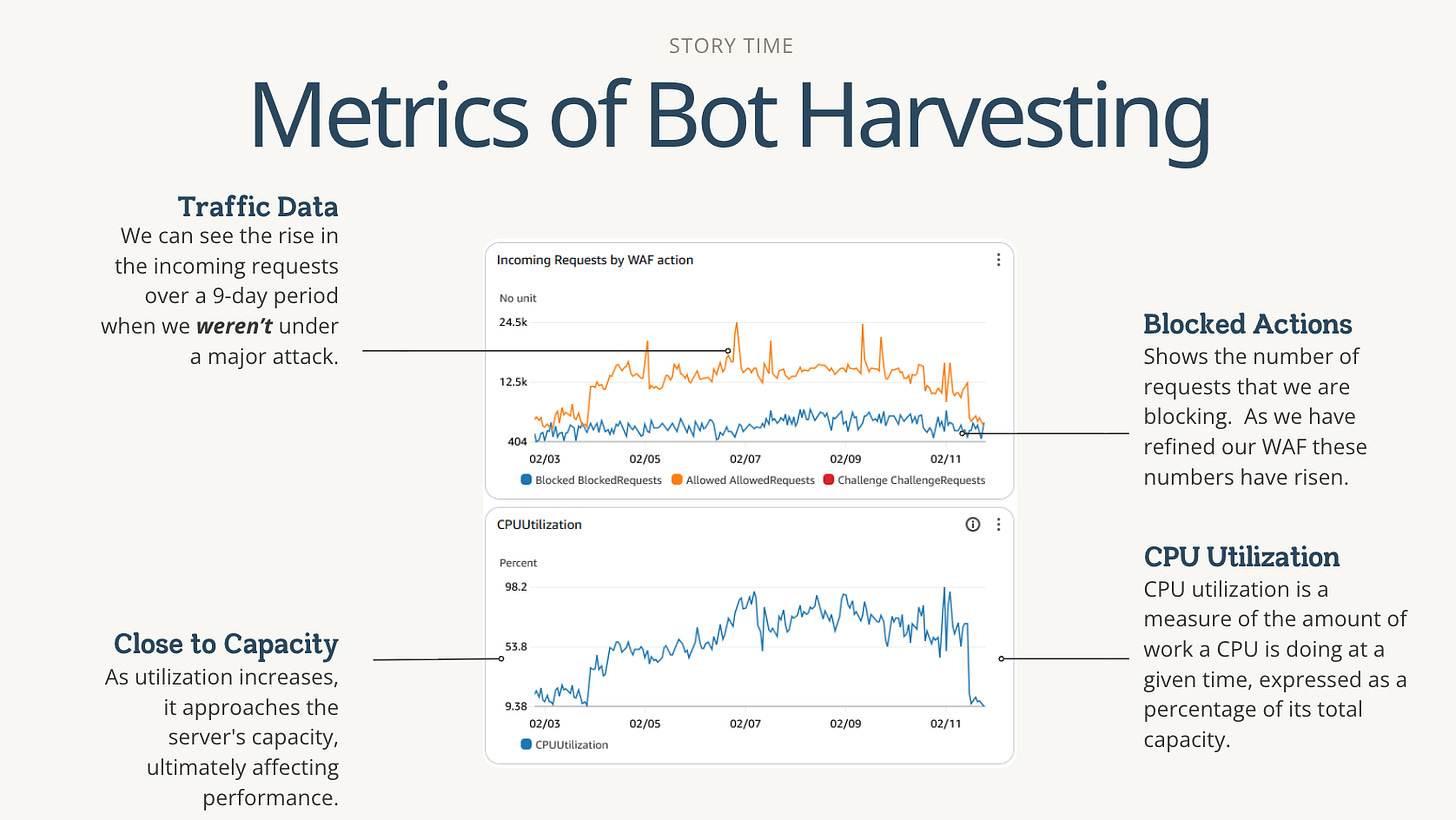

At Emory, we’ve spent years building digital collections and open-access repositories using various open-source infrastructure. But in early to mid-2024, I started noticing more outages across all our systems. We observed a substantial increase in web traffic. It wasn’t from students or researchers, but from obscure devices, and the traffic volume appeared unrealistic. Over and over, thousands of hits, all targeting our digital collections, open-access repository, and catalog.

At first, I thought it was me. Around that time, I assumed responsibility for managing the team responsible for on-call work after a manager left my team. I thought, well, maybe this is normal, and I’ve been oblivious to what is happening. But then, at a conference, a colleague from another institution had to step out of a session because their catalog was down, and we (administrators tasked with overseeing library infrastructure) all remarked that this was happening to many of us recently. I even had a vendor mention they had to increase their security spending because they were constantly under attack. Eventually, I realized that the situation was neither an attack nor a result of my obliviousness; it was simply AI training traffic. I’ve mentioned all of this before, so I will spare you the details, but if you’re new here, you can read all about it in a previous Substack post I wrote.

But the story doesn’t stop there. AI companies already have access to our content in other ways. In this video, I’m showing OpenAI’s chat interface; you can see it retrieving information and images from my institution’s digital collections. How did it get this access? Much of our content is available in the Common Crawl dataset, a massive web scrape that many AI companies use to train their models. So, of course, they have our content—and they are using it to generate information about our collections right now.

Update

A few months ago, after I began drafting this keynote but before I delivered it, I received an email from Google Books asking whether Emory University would like to join the project. I didn’t have the opportunity to discuss this with our University Librarian until December, but in the interim, Google released Gemini 4.

Upon its release, industry experts immediately touted Gemini 4 as one of the best models on the market, and OpenAI saw a significant drop in revenue as users canceled their ChatGPT subscriptions in favor of Gemini (myself included). Watching this unfold, I was reminded of that email from the Google Books project. I began to realize that Gemini’s performance wasn’t magic; it was high-quality data the company had acquired nearly 21 years earlier via the Google Books project.

But the Google Books project isn’t the only high-quality data the company has at its fingertips. Around the same time I received the Google Books inquiry, librarians across the community reported that representatives from Google Scholar were contacting libraries and vendors to ensure Google could easily crawl and index our scholarly repositories. It appears that Google was having difficulty crawling and indexing content in these repositories due to the aforementioned AI bot attacks. For context, most of these repositories contain theses, dissertations, preprints, and open-access journal articles from major research institutions worldwide.

While I don’t have definitive proof that Google is using data from Google Books or Google Scholar to train Gemin, I suspect Google long ago learned the lesson many other AI companies are now fully grasping: the quality of your data dictates the quality of your output. Or in other words, high-quality training data will create a high-quality AI model.

During a recent presentation to library staff—a talk much like this one—an audience member posed a fantastic and challenging question to me: “Why should we care?”

The answer is simple: these companies profit from, and will continue to benefit from, the labor that cultural heritage and knowledge workers have performed for centuries. While I have heard that some libraries have received one-time monetary reimbursements for some of this data, the data these companies acquire from libraries and museums is not a single-use asset; it is revisited, re-leveraged, and re-exploited whenever a company begins training its next AI model.

In addition to exploiting unseen labor in collecting, curating, describing, and maintaining these collections, their online activity to collect our data increases our infrastructure costs. For anyone familiar with technology, you’ll know that the majority of today’s infrastructure is cloud-based and billed using a per-use model. Increased usage directly translates to a higher bill. The more AI companies crawl our websites, the more our costs rise. These problems are not limited to cultural heritage organizations. Read the Docs and Wikipedia are also facing similar challenges.

At some point, something’s got to give.

Conclusion

What does responsible openness look like in a world focused on exploitation? I have extensively discussed labor and its devaluation. We need to return to our roots and reflect on why we valued openness and on our goals for it. In a world where most internet traffic is bots, does it still make sense to keep our materials openly available? If we aim to be ethical in our sharing—meaning we don’t want to provide people’s content to billion-dollar companies so they can become trillion-dollar corporations—who should we focus on, and what changes need to be made to make that possible?

How do we balance the desire to share information with the responsibility to protect it? At Emory, we have collections that focus on the Black experience in America. However, as a predominantly white institution, I personally question whether or not we are best equipped to understand how that content should be protected.

And even for the communities we are equipped to protect, such as our own, we’re struggling to engage in meaningful conversations around how much of our content we should share openly with billion-dollar companies. I also recognize that I am not in the majority on this issue and that restricting access is a radical concept for our profession. Still, I wish I saw more of these conversations in our ecosystem because I fear that our unwillingness to reevaluate this core tenet may lead to our eventual collapse.

References

Asparouhova, Nadia. Roads and Bridges: The Unseen Labor Behind Our Digital Infrastructure. Ford Foundation, 2016. https://www.fordfoundation.org/work/learning/research-reports/roads-and-bridges-the-unseen-labor-behind-our-digital-infrastructure/.

Holscher, Eric. “AI Crawlers Need to Be More Respectful.” Read the Docs, July 25, 2024. https://about.readthedocs.com/blog/2024/07/ai-crawlers-abuse/.

Mueller, Birgit, Chris Danis, Wikimedia Foundation, and Giuseppe Lavagetto, Wikimedia Foundation. “How Crawlers Impact the Operations of the Wikimedia Projects.” Diff, April 1, 2025. https://diff.wikimedia.org/2025/04/01/how-crawlers-impact-the-operations-of-the-wikimedia-projects/.

Skinner, Katherine. “The Emperor’s New Clothes: Common Myths Hindering Open Infrastructure.” Invest in Open Infrastructure, October 29, 2024. https://investinopen.org/blog/the-emperors-new-clothes-common-myths-hindering-open-infrastructure/.